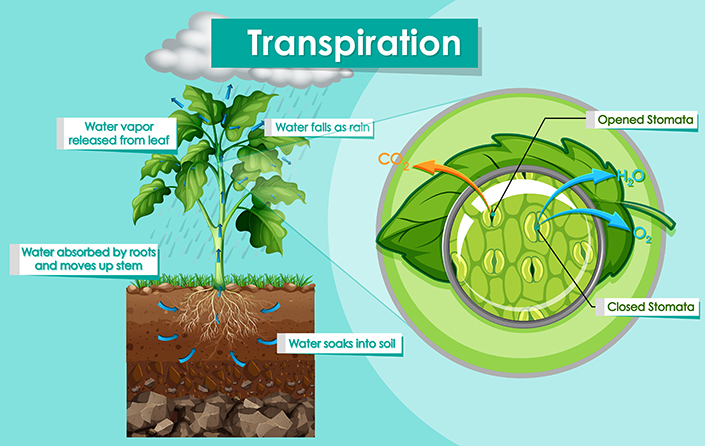

Transpiration in plants is a crucial biological process where water is lost as vapor from the aerial parts of the plant, primarily through the leaves. This mechanism not only helps regulate the plant’s internal environment but also plays a key role in nutrient uptake and temperature control. Understanding this process reveals how plants adapt to their surroundings and maintain balance in ecosystems.

What is Transpiration?

Plants absorb vast amounts of water from the soil through their roots. However, they use only a small fraction for photosynthesis and other metabolic activities. The rest evaporates into the atmosphere. This evaporation, known as transpiration, occurs mainly during the day when stomata—tiny pores on leaf surfaces—are open.

Scientists estimate that over 90% of the water entering a plant transpires away. This constant flow creates a pull that draws more water upward from the roots. Without it, plants could not transport essential minerals efficiently.

Types of Transpiration

Transpiration varies based on the plant part involved. Experts classify it into three main categories.

Stomatal Transpiration

This type accounts for the majority of water loss, often up to 90%. Water vapor escapes through stomata on leaves and stems. Guard cells surround these pores and control their opening and closing. In daylight, they swell with water, widening the stomata to allow gas exchange for photosynthesis.

Cuticular Transpiration

A thinner layer covers plant surfaces called the cuticle, which is waxy and somewhat impermeable. Yet, some water still evaporates through it, especially in young leaves or dry conditions. This form contributes about 5-10% to total transpiration.

Lenticular Transpiration

In woody plants, small openings called lenticels on bark and stems permit gas exchange. Water loss here is minimal, usually less than 1%, but it becomes significant in older trees during winter.

Mechanism of Transpiration

The process begins at the roots. Water enters via osmosis, moving from high to low concentration areas. It travels through the xylem, a network of tube-like vessels, upward to the leaves.

Cohesion and adhesion forces keep water molecules together and attached to vessel walls. As water evaporates from leaf cells, it creates negative pressure or tension. This “transpiration pull” sucks more water up, defying gravity. The entire column acts like a continuous stream.

Stomata play a pivotal role. When turgid, guard cells bow outward, opening the pore. Potassium ions pump into these cells, drawing water in and increasing pressure. At night or in stress, they lose turgor and close to conserve water.

Factors Influencing Transpiration

Several elements affect how quickly plants lose water. These can be divided into external and internal factors.

Environmental Factors

Light intensity speeds up the process by opening stomata and heating leaves. Higher temperatures increase evaporation rates, as molecules move faster. Low relative humidity creates a steep gradient, pulling more vapor out. Wind removes saturated air around leaves, boosting loss. Conversely, abundant soil water supports higher rates until depletion causes wilting.

Plant Factors

Leaf structure matters greatly. Larger surface areas transpire more. Thick cuticles reduce loss, while hairy leaves trap moisture. Root depth influences water access; deeper systems sustain transpiration in droughts. Plant age and species also play roles—succulents like cacti minimize it through adaptations.

Importance of Transpiration in Plants

This process offers multiple benefits. It drives mineral nutrient transport from soil to shoots, essential for growth. The cooling effect prevents overheating; leaves can drop 5-10°C below air temperature on hot days.

Transpiration maintains cell turgidity, keeping plants upright. It contributes to the water cycle, adding moisture to the atmosphere that forms clouds and rain. In agriculture, understanding it helps breed drought-resistant crops, improving yields without extra irrigation.

However, excessive loss can stress plants, leading to reduced photosynthesis if stomata close. In ecosystems, it influences local climates; forests transpire massively, moderating temperatures and humidity.

Global Applications and Impacts

Beyond individual plants, transpiration shapes planetary systems. It forms part of evapotranspiration, accounting for about 10% of atmospheric moisture. Climate change alters patterns—rising CO2 levels may reduce stomatal density, lowering rates but increasing water efficiency.

In research, tools like potometers measure it precisely. Farmers use this data for irrigation scheduling. Urban planners incorporate green spaces to leverage cooling effects, combating heat islands.

Conclusion

Transpiration in plants exemplifies nature’s efficiency, balancing water use with survival needs. By mastering its dynamics, we enhance agriculture, conservation, and environmental management. As global conditions shift, studying this process becomes even more vital.

FAQs

What causes transpiration in plants?

Transpiration occurs due to evaporation from open stomata, driven by environmental factors like light and temperature, creating a pull for water movement.

How does transpiration benefit plants?

It transports nutrients, cools leaves, maintains structure, and aids in the water cycle, though excess can cause stress.

What reduces transpiration rates?

High humidity, low light, closed stomata, thick cuticles, and adaptations in drought-resistant plants minimize water loss.

Is transpiration the same as evaporation?

No, transpiration is plant-specific evaporation, while general evaporation happens from any surface.

Can plants survive without transpiration?

Not effectively; it’s essential for nutrient delivery and cooling, but some adaptations reduce reliance in arid environments

2 thoughts on “Transpiration in Plants: Essential Process for Survival and Growth”